May 26, 2022

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

10:24 AM

| Comments (5)

| Add Comment

Post contains 537 words, total size 4 kb.

December 05, 2020

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

08:56 AM

| Comments (2)

| Add Comment

Post contains 98 words, total size 1 kb.

September 07, 2020

Whether it’s the swing, the waltz, or the two-step, what’s most important is that the partners are touching and in sync. They know where to go, what to do next. This connection allows them to enjoy the moment as one. They even look like one, because functionally, they are.

The man leads. He chooses the steps, but only in a sequence that she can follow. And the woman follows; she finds his lead natural, comforting, and protective. It has to be, because he’s leading her in directions she cannot see.

If either one withholds, the dance fails. So it is with the sexual encounter.

But if they relinquish their own wills, the pair can combine for an all-too-brief moment of glory demonstrating the beauty of human procreation: two complementary and opposite sexes united in forming a third, one greater than themselves, an immortality. 1+1=3.

Life.

It’s the closest we will ever get to knowing how it feels to be God.

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

05:00 PM

| Comments (1)

| Add Comment

Post contains 334 words, total size 2 kb.

October 26, 2018

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

08:21 PM

| Comments (1)

| Add Comment

Post contains 170 words, total size 1 kb.

November 04, 2012

Squinx, the elder daughter, has a fascination with all things space-related. She can pick out constellations and elaborate on the finer points of space dust and cosmic rays.

Why she cannot see her socks on the living-room floor, I cannot explain.

In any case, when I heard the annular eclipse would pass through Albuquerque, I packed up all the Rittenhousen for an adventure. We would meet Aunt #2 (we have 5) in the early afternoon, have lunch, view the eclipse, then crash at an airport hotel.

A winning plan, with the only variable being how much of Albuquerque (and, for that matter, North America) we would have to compete with for a good viewing spot. Surely, Bernalillo County would make room for us.

Our first task on arrival would be to test out the hotel's beds.

Next, the pool, ice machines, and elevators. All inspections: passed.

We met Aunt #2 at Chipotle, near enough to a college campus to see that the practice of "gauging" (that's French for "gouging") has resulted in some students' ear piercings opening large enough to permit thru traffic.

(Honestly, what happend to tattoos? Or rollerblading, for that matter? It's getting more invasive as time progresses.)

As the 4 o'clock hour approached, we would need to find a good spot to view the eclipse. Really, anyplace but a tunnel would work, but I'd been combing the local papers all day hoping to find someplace with an educational bent, so the kids might come away learning how an eclipse only happens every great once in a while, yet is predictable. A flight museum on the east side of town promised a pair of safety glasses in addition to live narration, so we set forth. And here we got a little lesson in why things happen as they do.

On our way out of Chipotle, the sling that Squeeky planned to hold Twiddles in for the viewing got soaked by a loose cup of water. The prospect of balancing a 2½-year old baby on her hip for the rest of the afternoon grated on Squeeky, so she hung the sling out the window of our rental car to dry, at least for the drive to the museum. As we arrived, she lowered the window, and at that exact moment an official on the ground announced via loudspeaker that all the museum's safety glasses had been distributed.

We would have less than 30 minutes to come up with a Plan B.

I dropped all the Rittenhousen at a nearby park and punched up a list of the closest auto-parts stores on iPhone. Racing to the first one, I scored a roll of limousine-black window film, then charged back to the park with 10 minutes left until the moon would begin to intercept the sun's broadcast directly over our little patch of real estate.

Between Aunt #2 and Nephew #4 we came up with a blade sharp enough to zip through the window tint without wrinkling. We figured six layers was enough to protect our eyes.

We had plenty enough film left over to pass strips around to others who hadn't planned any better than we had.

A photo of the eclipse itself would prove far beyond our equipment's capabilities. Here is something from National Geographic. It's exaggerated—the sun-moon combination didn't look nearly that large—but the photographer did capture the show's magnificence. You simply couldn't see it without an eyeshield; all you'd see otherwise was a strange sepia tone to the landscape around you. The color seemed atmospheric, as if a pall had been cast, gradually.

So, back to the metaphysical lesson. If that cup of Chipotle water hadn't been spilt, we'd not have been likely to have our car window down when the announcement was made outside the flight museum, and once we'd gotten parked and in a position to understand that Plan A was doomed, we might not have had enough time to carry out Plan B.

And all this was set in motion a billion years ago, when the moon began to spin around the earth.

I'll try to remember that next time I'm tempted to curse over plans gone wrong.

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

08:44 PM

| No Comments

| Add Comment

Post contains 697 words, total size 5 kb.

September 08, 2012

I want to teach my daughter how to drink.

No, seriously. Based on my life's experiences, there are too many pitfalls for her if I don't step up with some instruction.

So here are the rules:

1) Don't drink with the boys.

This should be obvious, but either it isn't common-wisdom enough or it's too easily forgotten. Nothing good happens when a girl drinks with the boys, not even with one of them. She will either find her inhibitions loosened wide enough for the big ugly monster called Regret to waddle in for an extended stay, or she'll throw up.

Which brings up the second rule.

2) Don't drink with the girls.

I'm thinking mostly of college-age girls with this one. The get-together starts as a hen party at someone's abode, then as the blender winds up the third batch, somebody has the brilliant idea to go clubbing.

I picture my daughter as the one dragging anchor, glaring at every popped-collar operator trying to single out one of her wobbly friends for whatever passes for dancing in 2020 AD.

If she's lucky, the good times will peak as she's holding the hair of her girlfriend kneeling over the toilet. Then she gets to drive the survivors home. (Note to self for 2019: Stow barf bags in the glove box of daughter's car before she leaves for college.)

3) Don't "not drink."

When the host asks what you'd like, have an answer. "I don't drink" sounds like a put-up, which is the same as a put-down because it's meant to make you look better at someone else's expense. If you really don't enjoy alcohol, ask for ice water with lime, and if anyone overhears that, say you have another day's antibiotics to finish off from your sinus infection. Otherwise, choose according to the decor, and make that one drink last as long as possible.

4) Drink your age.

Nobody over 30 should drink a margarita, except on Jimmy Buffett's yacht. Gin-and-tonic is for retirees. Beer is never wrong; also red wine, particularly if you ask for it by grape, as in "merlot" or "cabernet." Requesting a "Chilean white unless it's the 2011 vintage" is another put-up.

5) Drink pretty drinks.

No, not the foofy Day-Glo frozen thingies served in a vase with a toucan's feather. Drink what looks right on you. If you're in jeans at the rodeo, have a bottle of beer. (Make it a dark bottle so no one can see how much is left.)

At an office party, order a martini with tonic only; no gin, or just a splash. It'll taste just as bad, and no one will be the wiser.

Most other socializing calls for a glass of red wine. White's only good until it warms up, which means ordering another, which means too many. And too many is only for experienced professionals like your father.

Brown liquor is never OK. I learned that from television. It's for alcoholics and people who are just about to confess something horrible.

At home, I recommend port. On ice, with a twist of lime. Because your mother likes that, too, and she's pretty much the only other person on Earth you should ever drink with besides me and your eventual husband.

See also Last Call, or, I'm Kind of a Big Deal in the Martini-Drinking World

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

12:58 PM

| No Comments

| Add Comment

Post contains 561 words, total size 4 kb.

September 02, 2012

If you were guided here by Ace's Sunday Book Thread: Welcome!

You can reach me at rittenhouse dot michael at gmail dot com.

And, of course, you're invited to have a look around while you're here.

Michael Rittenhouse

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

11:42 AM

| No Comments

| Add Comment

Post contains 40 words, total size 1 kb.

June 17, 2012

Before I tossed these faithful servants, I wondered how old they really were. Carbon-dating's too expensive, so I had to go by circumstantial evidence.

- Was complimented for my taste in Avia sneakers by a guy I used to work with. Time frame: 2000-2009.

- Converted to "lawnmowing only" use. Acquired dog in 2001. (Think about that; it'll make sense in a minute.)

- Purchased new at Just for Feet. Went out of business in 2004.

So, sometime between 2000 and 2004 is my best guess for when I bought them. That means they lasted about a decade.

The chief economic benefit I can see from wearing shoes out this slowly is, my estate sale may bring in a few pennies more than expected.

Better take up running again.

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

05:29 AM

| No Comments

| Add Comment

Post contains 133 words, total size 1 kb.

March 21, 2012

My first paid job was stocking the warehouse of the busiest auto-parts store in Harris County.

A yellow-fronted throwback to the era of independent parts retailers, Charlie’s Hi-Lo Auto Supply occupied most of a strip mall behind a grocery store in the little West Loop city of Bellaire.

As a 14-year-old, my qualifications lagged, although I had more-than-average experience fixing cars. Technically, I was too young to be employed at all, but the manager knew my father as a regular customer, and being underage was the sort of technicality that people in small communities, such as Bellaire, casually agreed to overlook.

I would certainly never have been hired to work the Charlie's sales counter. That would have meant helping customers diagnose their cars' troubles. Of course, I wanted more than anything to work the counter. I’d accompanied Dad to Charlie’s dozens of times, watching in awe as the fast-moving young men quizzed him about his problem, flipped through their rack of parts catalogs, and sped off into the stockroom to fetch whatever he needed. They also advised him on installation as they handwrote a carbon-copy receipt and punched up the total on the store's sole cash register. All the while, they bantered with each other and even found time to tease me about how much of the work I would be doing after we'd taken our parts home.

I started at Charlie's the week after I finished eighth grade, and my mother even embroidered the company’s name onto a couple of blue work shirts so I could fit in with the counter guys. Unfortunately they’d all gone to polo shirts that year and I stuck out like a wannabe, the kid with his ball cap on sideways insisting he could play with the big boys. But as long as I showed up on time and kept moving while on the clock, I was tolerated. At least, in the stockroom.

said stockroom stretched across several storefronts whose glass had been obscured with a thick coat of auto-parts yellow paint. Behind them, dozens of library-style stacks held thousands of boxed parts and no small amount of dust, oil, and grease, all of it dimly lit by buzzing fluorescent tubes.

Like all the auto-parts stores, Charlie's accepted used parts ("coresâ€) for rebuild, which lent the place an old-oil smell and contributed to a layer of black gunk on the stockroom floor that could not be removed even if someone had cared to try. I shudder to recall that we sometimes ate lunch back there.

As the most junior employee, I got trash-can rotation duty, along with all the other filthy jobs. Taking the garbage out actually wasn’t the worst of them, as I simply set the cans on a cart, wheeled them out to the dumpster, and turned them over. Even packing the trash down inside the dumpster wasn’t entirely unpleasant because I could just lay flattened cardboard boxes across the top and jump on them.

No, the grubbiest job was sorting the cores: water pumps, alternators, starters, and other oily, grit-caked parts that customers brought in for exchange. The counter guys were too busy even to tote them off the sales floor. Instead, they flung them into a shopping cart, which I would empty every few hours. Each week the rebuild shops picked them up from wooden bins in our warehouse, but I wasn’t allowed to toss the parts into the bins, as there was risk of breakage when, say, one cast-iron water pump struck another. So I had to set them one at a time into the bins, grease, oil, antifreeze, grit, and all.

It never occurred to me to wear gloves. So I made good use of the wall-mounted Go-Jo dispenser, especially before lunch.

despite its obscure location, everybody in Bellaire who had ever raised his car’s hood knew Charlie’s. The store had rivals, but you always went to Charlie’s first.

This had everything to do with "kickin' ass," as the manager, Glen, described the speed and enthusiasm with which his dozen or so wildly motivated countermen moved auto parts. "Kickin' ass," he emphasized at the monthly staff meetings, "is what makes us the best parts store in town." Glen modeled this behavior every time he appeared on the floor, walking fast and barking orders, always on a mission, commanding attention and respect from the salesmen despite being the shortest male on the premises.

I don't know who introduced the word "shammer†to the employee lexicon—I never heard Glen say it—but all the guys used it to warn one another against feigning work. "You shammin’?†they’d accuse one of their own as they passed in the stockroom, when the poor guy was just quietly scanning a stack of parts for something his customer needed. "Can’t find a Victor VS-1039,†came the reply, in frustration that we might not have the valve-cover gasket that a customer would have to seek from a rival store.

We tolerated one of those stores directly across Spruce St., mainly because he didn’t do nearly the volume we did. His sales floor was polished and he sold fancy stuff like chrome wheels. Charlie's was all about 5-gallon drums of axle grease and floor jacks. Pretty parts were for special-order.

"I can handle three on the counter and two on the phone."

"Bullshit."

"Jimmy can't talk on the phone same time he's looking up for a customer. He gets all messed up and gives 'em the wrong answers."

When the phone rang, it didn’t matter if customers were lined up three deep and out the door; all the guys reached for the nearest handset. They'd karate-chop one side of it, popping it up off the receiver where they’d catch it and clamp it to their ear: "Charlie's Hi-Lo!" they barked, and you knew they would find whatever you needed, even if you didn't yet know what it was.

These guys knew their parts. When a stumped customer told how his late-model Pontiac wouldn't start or even run for long without a jump, the guys would blurt "7127" without even cracking the yard-thick catalogs before them. (That was the model number of the rebuilt alternator that fit most GM cars from 1971-1980.)

Dashing to fetch parts from the stockroom, they’d kick open the swinging doors — rather than push them — because they believed that helped them get through faster. (When the doors broke from time to time, Glen didn't bother telling his guys to stop with the kicking. He just patched up the doors.) But before leaving the counter, they’d assess the needs of at least two customers, saving themselves a second trip to the stockroom.

Although they competed with each other on speed, they would also ask one another questions to avoid selling the wrong part. After all, if a customer had to return to the store, that meant more work for everybody plus a mountain of embarrassment for whoever had sent the poor sap out the door with parts that wouldn’t fit.

They took personal risks, too. One of our in-house services involved a bearing press. That meant lining up a hardened steel axle with a 6-ton hydraulic press, adding pressure gradually until the bearing separated; then re-installing the new bearing on the same axle. The tolerance between those parts was "press fit"; it took tons of pressure to unite them. The guys worked the machine standing behind a sheet of plywood that had an eyehole cut in it, in case all that pressure suddenly made shrapnel.

At mid-shift the guys only got 30 minutes for lunch, which was just enough time to race to Taco Bell, or to Britton's for a burger. In between, they fortified themselves with Coke and Dr. Pepper from a machine I stocked twice a day. If they ran completely out of glucose, they could raid our Lance dispenser for a Moon Pie or cheese-and-crackers. They'd pay for it later with heartburn, but it was worth the pain, to them, to keep on selling parts.

business varied day-to-day at Charlie's. Saturdays were the most high-spirited and busiest, precisely because Bellaire's husbands and fathers had that day as their one opportunity to fix an ailing car. All day long, they trudged through Charlie's door in V-neck T-shirts or coveralls, toting a greasy engine part and/or a child that Mom needed out from underfoot for an hour.

On occasion—rain or playoffs, mainly—the customer flow eased, and the countermen's enthusiasm seemed to build, as if behind a dam. When that happened, they stunned the next customer walking in by himself, with every salesman on the 60-foot counter suddenly bellowing

"Hey, come on in!"

"How can we help you?"

"How are you, sir?"

"What can we do for you?"

His stunned look always prompted a round of laughter, and each of the guys automatically drew his pencil from behind his ear, ready to take down make, model, and year, for another dive into the catalogs before them.

In their shared sense of mission, the staff comprised a fraternity of sorts, establishing a hierarchy of merit based on who knew the most and could help the most customers in a day. There was also no shortage of hazing.

Another ritual, the WD-40 hose-down, required one employee to hold the newbie in a full nelson while another sprayed his groin with WD-40—a solvent that didn't hurt skin but burned membrane until it was flushed away with soapy water.

These rites went on amid a day-long exchange of homosexual innuendo. This ranged from outrageous statements designed to test one's reaction ("I'll give you a [sex act] if you'll work my Sunday") to random vulgarities. All the guys were militantly heterosexual, of course. The locker-room banter went on just to show who could be the rudest—yet another contest.

This being Bellaire, Texas, in the 1970s, however, the young men still had an unwritten knowledge of propriety: Four-letter words ceased when they entered the sales floor. Our churchgoing, suburban-dad demographic wouldn't have tolerated it.

any businessman would wonder what on earth motivated these employees to take such a proprietary role in a business whose stock they couldn’t even own. Countermen were paid by the hour, not by how much they sold. No benefits, no bonuses, and if they came back one minute late from lunch it would show on their time card and nick into their paycheck. Nobody could take more than one day off per week, aside from vacation. Our grubby workplace was decorated with nothing more eye-pleasing than boxes of auto parts. And, as I have noted, the store smelled like old oil, plus cigarette smoke from the half-dozen ashtrays set out for customers and countermen. Why did these guys love the place, the customers, the work, and the boss so much?

The answer is manifold. For one, they were working with things they cared about. All of them drove hopped-up cars and spent their wages on racing parts. Because they were customers themselves, no one had to coach them on how to treat other customers. They were the equivalent of computer nerds for the 1970s generation, but the knowledge gap between them and the customers wasn't so vast. They could communicate with the people they served.

Third, the countermen also competed and bonded with one another in accordance with their masculine nature. Because no one could know everything about every car, they learned to rely on each other for help: Rick was the electrical whiz; Blanchard knew Fords better than anyone else; Dennis was the go-to guy for transmissions, having rebuilt his own in his father's garage. They felt free to hone their skills and knowledge against each other every day; getting paid for it probably seemed like a perk.

Fourth, they were helping their own neighbors. All the guys lived within a couple of miles of Charlie's. The next customer to walk in could turn out to be their former scoutmaster, baseball coach, or algebra teacher. They got to know their customers by name—preceded by "Mr.," of course—and those customers returned the courtesy by learning the guys' names. You always felt that way about someone who had helped you solve a problem you couldn't solve by yourself.

I never heard of employee theft problems (with one exception, below) even though all the guys worked from the same cash register with no individual accountability. I guess they just regarded the money as Charlie’s, and wouldn’t dream of disrupting the good relationship they all had by stealing.

into all this camaraderie, and during the same summer I worked there, Glen dropped a bomb: a female counterman.

Susan’s femininity was never in question. Her slender build and straight blond hair made her attractive from all angles except straight-on, where an unfortunate case of pubescent acne had left her scarred in a way that makeup couldn't cover. What compelled her to seek a job in this male-dominated business, no one knew. She just showed up one day with Glen's blessing, and to my knowledge nobody was given any guidance on how to deal with her.

This presented the two assistant managers with a conundrum. To sustain the level of intra-staff competition that fostered Charlie's phenomenal customer service, all the men would have to compete with Susan as if she were one of them.

Problem was, men don't like to compete with women; rather, they are hard-wired to compete with other men. Furthermore, it was unthinkable to expect Susan to compete as one of them, with all the door-kicking, backstage language, and beer-drinking at the after-hours store meetings. And there certainly wouldn't be any ritual hazing or routine homoerotic taunting of this new recruit.

At the least, the situation would require the guys to pre-evaluate every word spoken to ensure they weren't committing a foul. Because even in the 1970s in Bellaire, Texas, men didn't swear in front of women.

The EEOC-approved solution to this conundrum would have been for all 15 or so of Charlie's male employees to alter their psychological make-up.

This did not happen.

their uniform and immediate reaction to Susan was to treat her as an undesired element.

If she approached two countermen talking, their conversation would suddenly stop. She never got asked along on a Taco Bell run. Any suggestion she made in store meetings got shot down by the guys, regardless of its merit.

One day, the guys' antics reduced her to tears. I’ve never seen anything so sad as a grown woman bawling alone amid stacks of auto parts, with no one to console her.

The manager simply couldn't shadow Susan every minute to prevent the guys from abusing her, and there was little he could do to make the guys control themselves. Susan left after four months, and should've gotten a bonus for lasting that long.

I can't defend the guys' actions, but I understand their resentment. This was a boys' club that also happened to be a place of employment.

Most times the guys could talk freely about whatever crude matter crossed their mind. Off the sales floor, they never had to self-censor, as they did at home.

They also competed, sometimes viciously, for status, and to drop a female into the middle of their party was not unlike adding a girl to a boys' sports team. If she bested one of them, he'd never hear the end of it; if they kept her at the bottom of the lineup, they’d look like brutes. There was no middle ground.

And the fact was, the guys did bury Susan sales-wise, but not necessarily on merit: The do-it-yourselfers walking into the store on a Saturday morning always gravitated toward the men, particularly if they knew one of them. A new female on the counter began with two strikes against her.

in my years since working at Charlie's, I haven't seen a workplace that didn't have similar tensions, at least under the surface. At a high-end investment-management company—the kind that doesn't advertise, because its customers just "know" where to trust their millions—I heard the young, male analysts openly disparage their sole female rival with misogynistic innuendo at every opportunity. She couldn't fight back because she just didn't have that kind of ugliness in her. And she couldn't tell the boss because his intervention would trigger a freeze-out—losing her access to the unwritten knowledge that distinguishes a successful analyst from a mediocrity. So she just took the abuse. In an eerie echo of my Charlie's experience, I once found her crying in her office after everyone else had left. She blamed family problems, but I'd overheard the guys earlier that day. She just wasn't welcome in a club she badly wanted to join.

that exclusive bond had its nobler aspects, at least at Charlie's. One was the guys' unspoken reverence for company property. Nobody ever thought about pilfering any of the expensive auto parts they handled every day.

Only one of the countermen I knew didn’t subscribe to this ethic, and he didn't mesh in other ways as well. Jimmy was cute, for one thing. Most of the other guys couldn’t get far on their looks, but Jimmy looked like Shaun Cassidy and was often taking "chick calls" on the phone. That was burr No. 1 under the saddle of resentment the other guys bore regarding Jimmy; that he didn't work as hard because he was "always" on personal calls.

By the time I started work, the animus between Jimmy and the rest of the guys had boiled over into a low-level war of conspiracy and mean pranks. The worst occurred when Richard, a generally likable Chrysler expert, left his new pair of boots in the warehouse one morning because they chafed him; he worked the rest of his shift in tube socks. When he retrieved his boots at closing time, he found that someone had planted a leaky can of transmission fluid in one of them. The smelly red liquid had wicked into the leather all the way to the top.

Over the next few days, Glen intervened to keep the peace, but Jimmy soon found himself a constant victim. For example, if he left a can of soda unattended, it would promptly become someone's ashtray.

The troubles came to a head one day when Jimmy approached me alone in the warehouse and asked, "Are you cool?"

"What do you mean?"

"Cool," he implored, "Are you cool?"

I had no idea what he meant, but I played along; what teenager didn't want to be "cool"? He handed me a small box of tools wrapped in a towel and told me to place it under the front seat of a certain car in the parking lot. I did as instructed.

The next morning Glen summoned me to his office. He sat at his desk, staring out onto the sales floor through a one-way mirror.

"Did you steal something the other day?"

"No, sir."

"Did you take something out of the store?"

The realization of what I'd done hit me.

"Jimmy told me to put something in a car for him."

"Thank you."

I never heard any more about it, and Jimmy never set foot behind the counter again. He came in later that week to pick up his last check, and the guys baited him viciously as he stood, grinning defiantly, on the sales floor by himself.

"What's it like being a FORMER employee?" they taunted, to which Jimmy responded with a denial no one bothered to hear. They kept at him, spoiling for a fight, until Glen's assistant rushed out with his check. Had this occurred after hours, he might not have escaped the premises without a beating.

unfortunately, I, too, left Charlie's on a low note. I'd given two weeks' notice before school started, and by the last few days Glen had already recruited a couple of other youngsters to replace me. On my last afternoon, the three of us were sweeping up deep in the stockroom when we paused a while to trade stories. One of the countermen passed by and, unbeknownst to us, took offense at our laxity and reported us to the assistant manager, who arrived seconds later and sent us all home. The newbies got by with reprimands; I was, however, branded a "shammer" and not welcomed back the next summer.

I never told Dad about this. Charlie's Auto had such a reputation that to have been rejected by its staff would have left an enduring mark on me.

See below for random notes, and see this entry for more on growing up in Bellaire, Texas.

more...

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

10:24 PM

| No Comments

| Add Comment

Post contains 4883 words, total size 30 kb.

March 03, 2012

One of our fellow parishioners is moving to Hawaii later this year.

I made sure she knows that anytime she wants to visit Dallas, she is welcome to stay with us!

You know, because I'm generous that way.

it's garden-building time at Rittenhouse Estates again, and God's having fun with my timing. (This will take a moment to string together, so sit down and have some patience, on the 'House.)

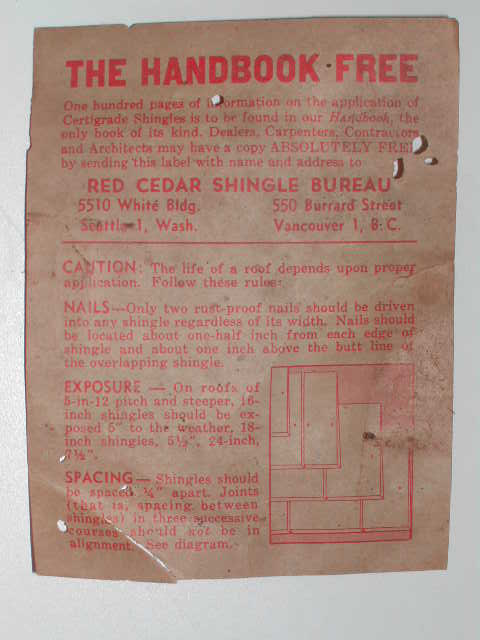

It began with hail, as all good biblical sagas do, a few months ago, when a hell-blast of ice balls pocked my ancient roof for the last time, and the insurers finally gave in: total loss, Mr. Rittenhouse, choose your contractor. I took the salesman who pestered me the least (there were a half-dozen of them roaming the neighborhood for weeks), and his crew made short work of my 1956-vintage cedar shake. Here's a wrapper I found in the attic.

In case you don't have a telescope handy:

In case you don't have a telescope handy:

One hundred pages of information on the application of Certigrade Shingles is to be found in our Handbook, the only book of its kind.

Paid to write that, someone was, in such a way that you can't help reading it in the voice of John Cameron Swayze.

Dealers, Carpenters, Contractors, and Architects may have a copy ABSO-LUTELY FREE by sending this label with name and address to

A street address follows in the style of "Seattle 1, Wash." I wonder what would happen if I mailed it in today. (Of course, they'd turn me down for the free Handbook, because I'm only a Writer.)

the roofer asked if i wanted to keep the narrow trim strip just under the roofline, and I said to take it off because I've had 100 feet of guttering out in the backyard awaiting my next free weekend for almost a year. But then I knew I'd have to paint, and before painting I've always wanted to flatten out a (barely perceptible) sag over the front porch, and before I knew what I'd gotten into, I'd put new cracks in two interior walls trying to straighten the blasted roofline.

Where God's timing begins to factor is, my neighbor chose that month to build into his garage and construct a separate one out back, and his contractor inexplicably threw out several lengths of 2x12 lumber in the process. I needed something 152 inches long to brace my roof after I'd finished leveling it.

I returned from the neighbor's dumpster with a board exactly 152 inches long. Plus two others, bolted together, that I used to jack up the overhang before I screwed it all together.

(I do regret not getting a snapshot of the two floor jacks and 4x4s I used to press this log into place. The neighbors had to look at that mess for two days.)

Then I glared at the wooden deck below. I'd laid this thing years ago, after tearing out a brick flower box, and never been satisfied with its look and feel. Pine 2x6s, stained and varathaned, they'd looked great for months until the finish evaporated and the boards' inherent springiness wore on my nerves. I wanted to re-do it with better lumber, but the cost of real redwood kept me just dreaming.

Until one Saturday when a friend called for help guiding a sewer snake under his rental house. Across the street, a building contractor was dismantling another early-'60s rambler. Not demolishing; dismantling. As he did, he'd removed a couple dozen 18-foot redwood 2x6s from the roof and laid them on the back patio. I satisfied myself picking through the dumpster for a few he'd judged substandard, and carted them home.

The next Monday, I got to wondering: What were his plans for those other boards? I drove over to find him setting the house's toilets on the driveway for salvage.

"How many you want?" he asked, and I told him I could use a dozen if they were at least 14 feet long.

"Go ahead," he gestured, "take what you need."

That's it. No price, just take the boards. I stood there for a moment, wondering if I should pinch myself. This was probably several hundred of today's dollars' worth of premium redwood, harvested about 1959. Yes, the boards had nail holes and smelled like an attic. But I could deal with that.

Of course, I'd be on my own for transport, and I quickly learned how to—and how not to—lift and load lumber longer than my Explorer onto its roof. The weight lent the luggage racks a precarious bow. I crept two miles back to Rittenhouse Estates with a wary eye on the bobbing ends stretched out over my front bumper.

Of course, I'd be on my own for transport, and I quickly learned how to—and how not to—lift and load lumber longer than my Explorer onto its roof. The weight lent the luggage racks a precarious bow. I crept two miles back to Rittenhouse Estates with a wary eye on the bobbing ends stretched out over my front bumper.

so that's how the front deck will get rebuilt for next to nothing, with redwood replete with rusty nails from the Eisenhower Administration. Redwood being a "soft" wood, I'd still have the sag factor to consider, and here's where that timing thing appears again.

Out walking Wolf Dog one afternoon, I glanced up the driveway of an unoccupied house and spotted two concrete piers, the foot-tall, 6,000-psi cylinders they place under foundations after leveling. They sat atop dozens of neatly stacked cinder blocks, looking like the sort of clutter a new owner would pay someone to haul away.

I dialed the realtor's number and left a message, asking if the owner would let me have those piers. He called me back the next day and said, Sure, take them, and take the 72 cinder blocks under them, if you want.

Fifteen minutes later, Squeeky came home and announced we were going to reconstruct our garden using cinder blocks, if we could just find some.

So we have a new garden.

Pictures of the new deck as soon as it's finished.

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

07:38 PM

| Comments (1)

| Add Comment

Post contains 981 words, total size 8 kb.

March 02, 2012

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

08:42 PM

| Comments (3)

| Add Comment

Post contains 149 words, total size 1 kb.

March 21, 2011

If you've seen this, you know what happens when I pray for money.

To make a long story short, my second career hasn't gone as expected, and since December I've been praying for $10,000 to help tide me over.

Guess what amount my boss offered me a few weeks ago, unsolicited, when I gave him my resignation?

this theme began in 1988, about one year after I graduated from UT and took a job in Washington, D.C.

I had underbid myself when I accepted this, my first employment offer, and within days of arriving in the nation's capital I realized I'd have to drop my car insurance so as not to run a growing deficit. To cope with the crunch, I cashed more than half my paychecks every two weeks and sorted the dollar bills into envelopes, alloting $6 a day for lunch and other sums for gas, groceries, and (hah!) dating.

So you can imagine how high I jumped when, nine months later, I was offered a job 120 miles away for 35 percent more money.

When I did the math, I could see no scenario where I'd get out of hock in less than two years—an eternity to a 23-year-old. My new boss had provided me with niceties I hadn't expected, like a walnut desk and leather chair in my own basement office with a computer full of the most advanced software I could think to request. But as I looked out over these luxuries, I realized I'd be willing to trade it all just to breathe again—free of the finance charge that bit a hole in my wallet every month, and did nothing for me in return.

I felt cornered. And although I wasn't very religious—I hadn't gone any further than to give my earnest, intellectual assent to God's existence—I felt, for the first time, completely dependent on him.

In that corner of the basement, behind my massive desk, I knelt and prayed to a God I knew was there but didn't know how to approach. I asked him for money, any amount, just something to help me get out of this dreadful muck of indebtedness.

The moment I stood and straightened my slacks, my boss strode into my office with a handful of envelopes, from which he extracted one and handed it to me, grinning. The look on my face conveyed my question.

"That's your bonus," he said. "Everybody gets one."

He shook my hand and zipped off to the next person's office.

This deserves a bit more explanation.

I had accepted an offer of employment with his personal, nonprofit corporation. His real job was heading a multibillion-dollar investment house, with a mutual fund and portfolios including the Nobel Foundation's. Guys on the floor above me bought and sold stocks each day for clients including some of the East Coast's richest investors, including more than one named DuPont. They created millions of dollars in wealth and took home decimal points of that, which was more than enough to keep them in big houses and high-end, imported sedans. All I had in common with them was a business address.

Yet, something compelled our mutual boss to cut me a "bonus" check after two months on the job. I remember, as if it were five minutes ago, sitting down to read the figures on the green safety-paper: $1,500.

The carpet beneath me still bore the imprint of my knees.

still, it isn't easy for me to pray, even when I know it works.

Prayer requires me to acknowledge that I don't have control of the situation. Try starting your day with that as your first thought. And yet, the best time to pray is a the beginning of the day, before the noise and ego get a running start inside one's head.

And with that thought, I'll move along and wait for my next prayer to be answered.

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

09:05 PM

| Comments (3)

| Add Comment

Post contains 736 words, total size 5 kb.

June 30, 2010

Contrary to what you've heard, London is not foggy and the British do not serve warm beer.

They do, however, still use the metric system except for driving miles—just one of my learning opportunities from 28 hours on the ground between London Heathrow and Newmarket, Suffolk, England.

Why such a long flight for a short stay? Easy: a concert.

half a lifetime ago i was cheated out of hearing the world's finest pop band in person when their saxophonist broke his leg somewhere between Louisiana and Texas. Why he couldn't just honk it out from a wheelchair I don't know. But once Spandau Ballet packed up their gear and flew home, they would never return to the U.S.

Then they sort of broke up after 1991, that is, if "having it out in court" equals a breakup. They remained at odds for almost 20 years, when perhaps the realization that there is no pension plan for aging pop stars began to sink in. Last fall, they re-embraced for a tour.

But they forgot to schedule a stop in Dallas, or for that matter anywhere in the Western Hemisphere. So to see them at least once before we are all in assisted living, I would have to go to England. Newmarket, Suffolk, specifically, at a concert following a horse race.

nine hours in a chair is too much for all but the most patient adults and dullest children, so I kissed the bright-and-beautiful Rittenhousen goodbye and boarded AA Flight 81 on a Thursday. I took my seat next to an off-duty flight attendant, who showed me the secret to obtaining free cabernet, which gave me sweet sleep for 15 minutes then catatonia for the next eight hours. I arrived at Heathrow feeling as if something had kept me awake in an uncomfortable position for a very long time, which is precisely what had just happened.

Then dawn came way too early. The English are on some sort of metric time, which is always six hours ahead of Central. Perhaps it's the 220V current that powers all their clocks. So on arrival I met bright daylight instead of the 3 a.m. gloom my body expected. I washed my face in an airport sink but wisely eschewed coffee. This was going to be a long Friday and I would need a nap at some point.

Whereupon I realized that while the British go to a great deal of trouble to transplant the steering wheel to the other side of every car they import, they leave the shifter right where it is. So I would not only have to drive on the other side of the road from the other side of the car, but learn to change gears with my left hand. Jetlagged. Beat. Maybe that upgrade to shiftless wasn't such a bad idea. At least the pedals were still in the right places.

I said my prayers and ramped onto the M25 around London. About five miles on I realized I had taken M25 the wrong direction. I figured London couldn't be that large so I continued, which seemed to make sense until an hour passed and I came upon a toll tunnel with nothing but American currency in my wallet. Not on the itinerary; not in their manual. Thank God for supervisors who can make magic happen for idiot tourists.

i am happy to report the british drive very fast on average, and those who don't still yield the inside lane. Freeway traffic flows like a river, the strong current pulling ahead while the backwater clings to the outside. We could learn from this.

And oh, yes, the roundabouts. They feel exactly like that Yes song. Unnerving at first but delightfully simple once you relax, stop thinking, and recite "Yield to the roundabout traffic and always signal."

Driving on the left actually proved to be just an intermittent challenge. Usually one can simply follow other traffic, so you're unlikely to get crosswise. My only foul-up occurred right where I expected, on a back street in Newmarket with no one to lead me.

It's the right turns that get you, unless you comply 100 percent with each of five steps:

- Look right.

- Look left.

- Look right again.

- Go completely past the lane your monkey-brain says to turn into.

- Drive right into the lane your panic-brain screams at you to avoid at all costs.

I muffed Step 4 and drove about 50 yards in the wrong lane, much to the astonishment of some chap following me. I corrected my path abruptly and pretended nothing happened, and fortunately, nothing did.

Such as: Like everything else in England, Newmarket takes about 1/3 the space it needs to be comfortable. I mean, I drove through miles of wide-open country to enter a town crammed hip-to-gutter with HO-scale housing. It's as if the vassals working the place were legally entitled to only 50 square feet per capita. The titled folk got all they wanted.

At the western edge of Newmarket the July Racecourse stretches out like a long J across low, rolling hills with three grandstands built along the finish line. The most desirable grandstand is, of course, right at the end, and it's the most expensive to enter. Money alone won't get you in; you've got to dress "smart." I wore the same navy sportcoat as on the plane but with a fresh white shirt, after a thorough shower.

Newmarket ticket prices don't pinch because the betting windows make the margin. I don't gamble, not because I think God forbids it, but because it's a fool's errand. Fiscally speaking, I would rather hold shares in gaming companies than supply their revenue.

Still, as I passed one of the trackside betting kiosks I spotted horse No. 9, "Louisiana's Pride," and since I was born in Louisiana (and although they still haven't named anything after me), I placed a £5 bet.

Minutes later a mob of running horses thundered over the hill toward us. I looked up-course just in time to see one of them showing hooves where its ears ought to be, followed by a shower of divots. The crowd reacted, "Oh!" but the pack continued on. As they passed the grandstand I fished out my ticket to see which number my horse was. I looked up again just as my chosen No. 9 galloped past, sans jockey, who was still on the ground where he'd been dropped in all the commotion. Medics hoisted him into an ambulance and he was later reported to be all right.

About 8:30 fans started gathering before the stage, so I took a spot about four rows back. No seats; we would stand for the whole show. After nine hours' sitting overnight I could deal with that. Overcast skies and temperatures in the mid-70s made the evening perfect for an outdoor show.

To my mind there were two Spandau Ballets: the club version, which made poor use of Hadley's voice and never got across the Atlantic; and the later MTV sensation, in which the boys donned fancy suits and the single "True" conquered pop charts worldwide.

I was surprised to hear five songs from the album Parade, which followed True in 1984 but lacked a hit single. The band peeled off "Highly Strung" and "Only When You Leave," then the very sexy "I'll Fly for You," which I don't know how author Gary Kemp can get through without smirking at all the girls in the crowd who'd like to be, um, "flown for." Kemp is also supposedly responsible for including "Round and Round," a delightful romantic memoir and minor hit, in every show. I would have been disappointed not to hear it.

for those who only knew the band from its mid-80s videos, Spandau Ballet was all about the handsome Tony Hadley. His soaring vocals made "True" and "Gold" enduring singles. In this concert, Hadley managed his part well until "Through the Barricades," a title-track anthem he delivered masterfully on the album but destroys in live performances with a vaguely Shatner-like narration in lieu of singing. I ignored him and focused on Gary Kemp, who wrote "Barricades" in the first place and really should take it back at this point.

I loved this single the instant I heard it way back in 1986, and have never tired of it. The song inspired me to buy a guitar and teach myself the melody. The lyrics refer to T.S. Eliot (among other poets), and some years back I came across a rare book of Eliot's epic poem "The Waste Land," which included a facsimile of the original manuscript and penciled-in notes from Ezra Pound. I mailed it to Kemp along with my best wishes; he responded with a heartfelt thank-you.

The band went on to deliver the crowd-pleasers "True" and "Gold" before taking a big, long bow; this was the last stop on the tour. They promised to be back, and as I searched for my car in the grassy field next to the horse track I passed a carload of fans who'd propped open their hatchback and sat drinking wine while a CD from the tour played out loud. Spandau Ballet will have no problem filling stadiums again if they return as promised.

i drove back into town to Byerley House, a delightful bed-and-breakfast, with my hearing intact thanks to the wax I'd shoved into my ears before the show. Despite being awake for most of the past 24 hours I could not immediately sleep. I chatted with a few understanding Facebook friends, who tolerated my babbling about the program and wished me a good night.

I got four hours of sleep, rising at 5 a.m. having agreed the previous afternoon to breakfast at 8. With nothing to do until then I drove to the Newmarket town center for some photographs, then out to the horse country for more.

Byerley House deserves a little more praise here. "Breakfast included" has gotten a bad name in the States because now that everyone offers it, it's become a lowest-bidder commodity. Read that: cheap carbs.

So, the cooked-to-order eggs, ham, sausage, and potato I was handed at table reminded me of the old British custom of leaving a small amount of food on your plate so your host wouldn't worry you'd been underserved. I blew that off and wolfed every speck, then moved on to the cold cereal and more fruit than I deserved to choose from. The French-press coffee left me feeling as if I were among the landed gentry, or something royal. I checked out regretfully, ready to stay a while and send for my family.

Two hours later I lined up at Heathrow for a flight home I barely remember. Westbound trans-oceanic legs usually mean arriving the same day as departure, but the day ends six hours later than expected. Sleep almost never happens for me on such flights, despite my packing a neck pillow and blindfold. What I really needed was elastic wrap around my head to keep my mouth from falling open; dry gums are their own alarm clock. Also, American should tint their windows.

On arrival this time I didn't start crying at Customs. Family awaited me outside, and I've rarely missed them so much.

i may return to britain someday, but for now I'll be content with my Spandau Ballet CDs and memories of a cool summer evening spent literally rubbing shoulders with my people, my fellow fans. Should the band ever grace the States, I will be there.

I know that much is true.

Here's a pan of the finish line from the Premier Enclosure.

A fish 'n' chips in Newmarket where I dined before the concert. In foreign places I like going where the regular people go.

Architecture in Newmarket.

Amber waves of grain in the incubator of representative democracy.

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

08:07 PM

| Comments (1)

| Add Comment

Post contains 2458 words, total size 20 kb.

May 02, 2010

We're supposed to laugh out loud once a day, right? Saturday, I got cheated.

Last Friday night I had the great fortune to be invited to Sarah Palin's appearance benefitting the (Dallas) Uptown Women's Center. At dinner's close, I was handed a card and envelope, which surprised me: This hadn't been explicitly billed as a fundraiser. Still, I said a quick prayer, unfolded the "emergency" check from my wallet, and filled it out.

Good causes are best funded that way, with little deliberation. Although I am not a wealthy man, I lead a comfortable life. Many others don't. So I left feeling okay, though a bit apprehensive, because I'm not in the habit of writing checks that big voluntarily.

Shift gears with me for a moment; this is a transition that will make sense when you're done.

You know how the government's paying Americans to buy new appliances this year? I signed up for the rebate, because our refrigerator is hot. I mean, the unit chills just fine, but the motor windings have shorted into the case, making the outside of the fridge a literal live wire. I tested it after Squeeky felt a mild shock when accidentally touching the sink at the same time as the fridge. My voltmeter, retracing her path, showed 118v AC current between the sink and the appliance.

In short, I am blessed not to be a widower.

So when I heard about the government appliance rebate, I went shopping. Bought a handsome new Maytag with the freezer on the bottom so we don't have to stoop all the time.

Saturday morning, two guys arrived in a truck. One came to fetch the danger-fridge while his boss unboxed the new one. Boss-man lifted the cardboard off the new unit and immediately zeroed in on a blemish way down low on one side, near the back. He pointed to a scratch that had been painted over somewhere up the production line. He said, "I give you $100 for that," and I thought he was kidding.

Then after he wheeled the fridge into my kitchen, he wrote just that on the invoice and handed it to me for a signature.

"If you don't get your check within two weeks, you call this number."

Okay.

Okay. Do you see what happened there?

That is why I wanted to laugh out loud. But I couldn't, because it would have confused the guys.

So after they left, I sat down and had a good snicker.

And that is why I believe in the power of prayer.

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

08:11 PM

| Comments (1)

| Add Comment

Post contains 431 words, total size 3 kb.

February 14, 2010

I'm auctioning off some U.S. coins my father collected over the years—pre-1964 silver, nothing all that rare—and got down to the quarters and dimes when something gave me pause.

A 1952 dime, to be specific.

I pondered how that little Roosevelt had roamed the country at a time when 10 cents meant so much more. Perhaps, in its days going from pocket to pocket in America:

- It clicked through any number of red Coca-Cola machines, settling in a metal box until some fellow named Jake in coveralls came to retrieve it.

- A railway clerk used it to free a stuck typewriter key.

- A banker fingered it as he waited to testify before a congressional subcommittee. Later, he bought a cup of coffee.

- It served as a tip for a shoeshine boy in the lobby of a Cleveland office building.

- And who could count the number of phone calls it paid for?

Men wore hats then. Pocketwatch chains were a sign of age, or seniority, or both. Suits were standard downtown, and in the country they marked you as a stranger, except on Sundays.

Civil Defense signs reminded us that we still had enemies.

Civil Defense signs reminded us that we still had enemies.

When a guest in your home fished out his cigarettes, you got him an ashtray—even if you didn't smoke.

Nobody pumped his own gas.

at some point each of these coins wound up in my father's hand, where he noticed the date and decided to place it in a ceramic piggy bank he kept high in his closet. Every once in a while he'd get it down and we'd look through them together, sort them, arrange them by size and year. He had me read the little ones, though at the time I didn't understand why. I'd always have to ask who the figures were, and he'd tell me, and I'd forget. All I remembered was that Kennedy replaced someone on the half-dollar in 1964. All the others had more continuity.

Yes, I know, it's ridiculous to feel so much sentiment for a few dozen coins of the realm. Yet, as I sit in this house—which went up during the Eisenhower administration—and ponder the labor that made it possible, I realize coins like the ones on my desk served as another part of that very exchange. At some point those workers traded sweat for the quarters and dimes that ended up in their pockets. They're all dead now and and the house will someday fall down. But the currency remains, having outlasted what it was traded for.

There's more to these coins than symbols stamped in silver. I'm going to hold onto them for a while.

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

05:04 PM

| Comments (1)

| Add Comment

Post contains 440 words, total size 3 kb.

December 31, 2009

I like clever people, and I especially like the ones who tell stories of their own cleverness without making it sound as though they're bragging. I always learn something from people like that.

The following was told to me by an acquaintance, many years ago, in another state. I'll leave his name out to further protect his modesty.

he was the managing partner in a restaurant situated several miles outside of town. The place had a country-club feel, being isolated out there in the hills and trees, and the city's leading businessmen liked it because the tables had lots of space between them. It was where you'd go for lunch if you valued your peace and privacy, and if you were the sort who didn't blink at the menu prices.

He served fine food, including foie gras, and this got the attention of the local animal-rights nuts, who scheduled a tantrum in his parking lot. They notified him ahead of time—mighty thoughtful of them—and although they said they only wanted to "call attention" to the inhumanity of serving goose liver, he worried. Would his exclusive, low-profile clientele be put off by the spectacle, perhaps never to return?

There was no stopping the protesters. They would set up on the driveway, which by this state's laws made it illegal for him to have them removed unless they actually prevented him from doing business. He had another driveway, so the cops wouldn't touch them.

He would have to rely on his wits.

one day prior, he called his plumber.

"I want you to send one of your guys out here at 9 a.m. tomorrow morning. He absolutely has to be on time, and he has to be in a truck with your logo on it. I will pay your hourly rate, and all I want him to do is sit in my restaurant and enjoy breakfast and a newspaper until I let him go. You can't breathe a word of this to anyone. Deal?"

The plumber agreed. In fact, he would handle the job himself.

The partner also called his best waiter and asked him to show up two hours early that day. No explanation; just be here in uniform at 9 a.m., prepared to serve. And so he did.

The restaurant didn't open until 11:30, but on that cool autumn morning it didn't technically have to be open for what was about to take place.

while the waiter served the plumber breakfast, the partner stood in the foyer, watching the parking lot. When the first of the protesters showed up about 10 a.m., he stayed put. When a TV news van appeared at 10:30, he signaled to his waiter.

The partner walked out to the news crew and let them know they were welcome to film all they wanted, and that he would answer any questions they had for him, but not on camera. The protesters stood shivering nearby while he gave a full interview, and the reporter took notes.

Then the partner greeted the protesters, shaking hands while the camera rolled. He gestured to his waiter, who emerged from the restaurant with a tray loaded with fine breakfast pastries. He also delivered them an enormous coffee pot full of his finest blend. The protesters and the news crew delved in.

"Not a coffee drinker? Would you like tea? Yes, we will bring you some tea."

As the protesters began to tell the partner all their grievances, he stood silently, nodding, and the camera took it all in. After a time, having said all they wanted to say to him, they started passing out their placards to wave at any patrons who'd be showing up soon.

And right about then, dams began to bulge.

The protest leader, who for 20 minutes had been explaining to his host what a barbarian he was, re-approached him with a neighborly request: May we use your restroom?

"I'm sorry, fellows. The plumber is still here. The bathroom's off-lmits until he's done."

With that, he turned to the reporter.

"Do you have all you need from me?"

The journalist nodded.

The partner thanked his guests, shook all their hands, then helped his waiter carry the coffee, tray, and dishware back into the restaurant.

within 10 minutes, the reporter had finished his "on the scene" shot and the crew started packing its gear. The protesters fidgeted aimlessly for a few minutes, then began piling into cars to seek the nearest bathroom. They would need to go several miles for that. By the time they'd relieved themselves, they agreed their day's ends had been accomplished, and went home.

The restaurant's patrons began arriving for lunch a short while later, having no idea anything had occurred there that morning. Some heard later about a news report on local TV that day, and they shrugged.

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

08:57 PM

| Comments (1)

| Add Comment

Post contains 820 words, total size 5 kb.

December 27, 2009

Actually, that should read "fatality-free." Since Little Roo's arrival three years ago, we've had two emergency-room visits after things collided with his head.

Although our safety record is otherwise superb, I do what I can to keep our insurance agent nervous.

like a couple of weekends ago, when I rented a 19-foot scissor lift to help me reach several big dead limbs hanging over the house. While I have the toughest roof in Rittenhouse Estates (two hailstorms, two denied claims), I doubt the rafters could take a 15-foot log without caving.

Several such Swords of Damocles angled precariously off the big elm out back, waiting for a pudgy sparrow to trigger cataclysm. And of course there was the great Taurus spearing of last summer to remind me how ugly things can get around here in a storm.

In nature, elm trees shed wood all the time. Higher limbs hog the sunlight, and lower limbs die and fall off. But in nature, humans live in caves rather than costly, fragile structures under 50-year-old trees. So the elm would need a trim.

Surprisingly crude-looking, isn't it? Mechanically, it's nothing more than a hydraulic jack laid sideways between steel scissors with a platform bolted on top. For moving it around, an electric motor supplies one-wheel drive. The working floor scales to 19 feet and can extend a sort of diving board off one end. No safety belts, no cover, and no fiberglass in the structure to insulate against power lines. A tort lawyer's dream, and yet, these things are used everywhere.

The rental-yard guy showed me the buttons and, after hitching up the trailer, wished me well. No caveats, no warnings. Could it be that safe?

the answer is "no," if navigating from the trailer to the backyard proved anything. I learned too late that the controls were detachable, making this the ugliest remote-control car I've ever driven. Having the joystick with me on the ground certainly would have simplified getting through the back gate, which is exactly 1.01 scissor lifts wide.

With me atop the platform, the controls worked a little too well. When I tipped the stick forward, the machine lurched ahead, pitching me so that my arm pulled back hard on the joystick, reversing power. That stopped the ride so suddenly that I toppled forward, again tipping the joystick with me. The to-and-fro grew so violent that I had to release the controls and just grab the railing until everything stopped.

Once on the patio, getting myself up into position called for the spatial thinking of an airplane pilot, so that I didn't elevate my head right into a branch, or, on the way back down, take off a rain gutter. I learned to feather the controls and take frequent looks around while moving.

But for my speed, an observer might have been hard-pressed to tell me from a professional. Except I forgot to check the weather report.

Oh, yes: We got rain.

After draping a sheet of plastic over the machine, I sat for a while, staring like a glum soldier at all the work I couldn't do. In the back of my mind I heard a meter running: $100 a day, or about $10 per daylight hour. Tick-tock, cha-ching.

Rust be damned. I found a poncho and rubber gloves I went back up and at it.

The hard hat wasn't for falling objects; you don't usually cut things above your head. I donned it to keep the poncho hood on tight. But it ended up saving my skull the next time I catapulted myself up the ladder onto the platform, forgetting there was an iron railing around it. Bang.

Once I got chest-level with the first limb (about 22 feet up), I buzzed about a yard off it, catching the piece with one hand. So as not to crack the patio, I lobbed it into the backyard, making an impressive divot. Squeeky captured one on first bounce.

Falling logs wasn't the biggest danger, though; it was the bounce-and-ricochet. Sole casualty: a terra cotta pot (visible above in its last intact moments) that failed to move in time.

In this sort of operation, the chainsaw does all the hard work, but you still have to hold it tight. Very quickly, my hands began to cramp, and that caused the biggest time-burner: stretching and resting my forearms after buzzing through each log.

why not hire a pro to do this? For starters, it's too dangerous. No, really: An insured, bonded professional who accidentally drops a log through your roof still has to file paperwork, and then there's the adjuster, and the bids, and the roof leaks the whole time, and before long, you've taken enough time off from work to deal with the whole mess that you might as well have done the damage yourself. I believed I would take more care to saw these limbs off a piece at a time than any paid professional would—and for about 1/4 the cost.

Dallas has no shortage of paid non-professionals, too. I know because for weeks, they've been stopping by our house in pickup trucks, eyeing the lumber dangling over my roof, eager to sling themselves up there on ropes and hack it down. Maybe I'm a fool, but I would rather take the minimal risk of pruning the tree myself than to pay the liability for injury to one of those guys. Too many hungry lawyers out there.

And you have just witnessed a demonstration of Rittenhouse's Third Law. I gave you three sham reasons while concealing the fourth, correct one:

I like doing this stuff.

by the time i was done, HO-scale Lincoln Logs littered the landscape. The backyard looked as if a very polite tornado had passed through, slicing trees into firewood-sized chunks rather than breaking them.

Amazingly, by the time I motored the lift back onto the trailer, no injuries had occurred. Yes, even after taking the kids up 19 feet for a look-around at the neighborhood.

Having whetted their appetite for heights, I followed up the next week with their handmade Christmas gift: a 12-foot rope ladder.

Eight hardwood dowels and 150 feet of rope. A merry Christmas for everyone except the toy companies.

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

09:13 PM

| No Comments

| Add Comment

Post contains 1043 words, total size 8 kb.

November 11, 2009

The following is a guest post from my sister, known to you in the comments as DawgMom.

Recently my husband and I attended the 82nd Airborne Convention in Indianapolis. There were retired paratroopers, active duty paratroopers, wounded paratroopers, paratroopers who looked like they didn't shave yet, old paratroopers … you get the picture. We didn't know exactly what to expect, this being our first convention, but I knew the beer and the stories would flow freely.

I've never laughed so hard and so long. And cried some, too. The guys we were with had not seen each other in years. It was amazing how quickly they fell into the camaraderie of their glory days. They had a bond that would stay with them all their lives. Of course, the stories abounded and since most of them were laced with initials standing for weapons, divisions, equipment, ranks, and myriad mind-numbing combinations of such, my attention wandered and I started studying people.

The old guys broke my heart. There were proud old warriors from WWII! Imagine that, something we read about in books and see in movies. They hobbled along, still with a saunter in their gait, moving up close to each other, rheumy eyes gazing into the same. They would wrap their arms around each other and nod, almost touching foreheads in long moments of silence. When the flag passed by, they slowly got to their feet and saluted, their posture erect, their arms straight.

Then there were the guys who were in Vietnam and the Dominican Republic. They are from my era. Now here were some hard drinkers. They were watchful, with heavy, lidded eyes and could be very still, almost eerily so. A lot of smokers. There was a whole table of the Golden Brigade from Vietnam. They made a special toast each year, and each year the table got smaller.

The young guys had returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Some were going back the next week. So full of energy, they bounced in and out of the hospitality suites, always searching, alert for the next excitement. They were strong and vital and just so damn young, their faces unlined and shining with life. They called the men "Sir" and the ladies "Ma'am." They trailed behind the storytellers and hung on every word, their eyes avid with fascination.

But it was to my husband's group that my heart belonged. These men had been to war, had relied on each other for their very lives. They had been in Panama, Honduras, and Desert Storm. They were cocky and smooth and arrogant and sure of themselves. They had an easy banter and ready laugh and loved each other without end. I watched them move through the crowd with that innate paratrooper swagger that I knew so well. These guys were so attuned to each other, even after all these years they still moved as a unit.

One night during a ceremony, I looked around the room. These men, these soldiers, loved their country and their flag unabashedly and with all their heart. They would defend either, without question, with honor. And as I gazed up at my husband as he stood ramrod straight and stock still, I knew that this man, here beside me, would give his very life for me.

And there, is my heart.

In observance of Veterans' Day, fly your flag. And if you will, please observe the Armistice Day tradition: two minutes of silence at 11:11 a.m.

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

01:06 AM

| No Comments

| Add Comment

Post contains 595 words, total size 4 kb.

October 24, 2009

When I can hear traffic from the Interstate two miles away, I know autumn has returned.

Temperatures, you know. Colder air conducts sound better. I wonder if farmers wake up to the dull roar from a distant highway and know it's time to harvest.

At Rittenhouse Farms, it's jalapeño time.

Our first garden produced a bumper crop of these. Also some miserable cherry peppers, which no one likes. The banana peppers came in strong, but the tomatoes only reached marble size before season's end. Now I know why people start tomatoes as plants, not seeds.

The basil, however, outgrew its progenitor.

it's been an exceptionally fertile season at Rittenhouse: We had another baby. I haven't come up with a good pseudonym for her yet (see "Who Lives Here?" in the right margin). With the third of three, it's tempting to give her a diminutive like Bitty, but those have a way of sticking through adulthood and perhaps fostering a resentment that will send her into the arms of a dirtbag, or to welding school. Besides, she wasn't "bitty" at all: 7 lbs. 5 ozs., for those keeping score at home.

We hired a midwife this time, having seen enough interventions from what we believed were "granola" gynecologists. This lady has less med school than a doctor, but more instinct. I watched her closely during Squeeky's 75 minutes of heavy labor, and there was a moment where her demeanor changed completely. If she'd been at bat, she'd have planted her spikes in the dirt. Preparing for a heist, she'd have ground out her cigarette, lowered her hat brim, and muttered, "Let's go." She knew Squeeky's next push would be the last. And so it was.

As these things go, the birthing went uneventfully. Healthy baby, healthy mama, the latter having earned my eternal respect and admiration for bearing all three of our children without anesthetic. We hit a minor bump with the hospital staff, but later heard praise from them for declining all the standard practices that invade a newborn's bloodstream and separate him from his mother. Granola Republicans, I guess we are. Odd birds no matter who's looking at them.

So, Squeeky's mom is in town, and the Rittenhousehold is consuming toilet paper at a ferocious rate. I know that's a standup cliché, but sometimes life affirms standup. A house full of women goes through bathroom tissue exponentially faster than a house with the same number of men. I can hear the rolls spinning as I write.

Or it might have to do with the volume of food we're consuming. I get all weepy at the sight of a refrigerator stuffed with packages from friends, neighbors, and parishioners. If Facebook facilitated food gifts, I'd have to store them off-site.

naming our children has always been a schizophrenic undertaking, because we never try to find out the sex ahead of time.

It's also a breathtaking act, when you think about it. To name someone is to exert power over him; this was openly acknowledged by the ancient Hebrews, when Adam named every creature on earth as God presented them, putting them under his dominion. I've rarely felt so magnanimous as when the hospital staff hands me the clipboard and leaves the room: Today, I will name someone, for life.

Anticipating another daughter, we'd toyed with the botanical Jasmine. Ulitmately I demurred, because the second daughter is supposed to be the rebellious one. She can't ever quite get the same attention as Number 1, so she tries harder. I pictured "Jazz" in late adolescence, spending a little too much time with the boys, head cocked and smiling in her jeans, fingers twirling a lock of butterscoth hair.

For sons, some families have a tradition of using the wife's maiden name as his first name, then going by his middle name. That's how you get boys named Pendleton James McKay, whom everyone calls "Jim." Too complicated for us.

This one settled the matter by turning out concave rather than convex. We went with a name that Squeeky heard in a dream, and it happens to be that of a girl I adored in junior high, who was two years older and rode the same school bus. She brushed her hair at least twice on the way to and from, and it always shone like gold.

A little golden dream. Soon as I can spin that into a pseudonym, I'll name her for you.

Posted by: Michael Rittenhouse at

08:32 PM

| Comments (2)

| Add Comment

Post contains 742 words, total size 5 kb.

September 17, 2009

i stepped into the cape town tobacconist's shop and immediately got an earful from the owner.

Perched on a stool just inside the door, he looked as if he hadn't moved in about 10 years. With a cell phone clamped to his ear he let loose on some government official who—I gathered as I studied the selection in this narrow, old store—wasn't able to locate his son.

None of my business, of course, but when angry words fill the room you're in, you can't help but follow the narrative.

A clerk assisted me in picking out several cigars. As she rang up my purchase, the owner finally flipped his phone shut and sighed.

"My ex-wife," he said directly to me, as if we were on a first-name basis. "She took my son, right from the caretaker's, just walked off with him. And these people won't go and get him from her."

I nodded, then shook my head, the international gesture for Bureaucrats: What good are they?

"I pay taxes on everything I do," he continued, "and this woman, this drug addict, she laughs at me, steals my son, and nobody will do anything."

Something clicked in my mind about then. In all his ranting, there was no mention of the boy's welfare. It was all about this fellow, the father, and how he'd been inconvenienced and insulted. I gathered my receipt and bag, and paused to address him.

"What's your name?"

He suddenly looked me in the eye, as if a veil had fallen from between us.

"My name?"

"Your first name," I clarified, motioning to the clerk for a pen and paper.

"Grissly."

I leaned forward and wrote that on a scrap of paper, then tucked it into my pocket.

"I'm going to pray for you, Grissly," I announced, "and your son."

He seemed about to scoff, then caught himself. An uncomfortable moment passed. Then he spoke, very calmly.

"One of my school friends, he became a priest," he said. "He says he prays for me. I don't know."

"That makes two of us, Grissly. I wish you well."

He took my proffered hand and shook it. I returned to the busy sidewalks of Cape Town.

so i prayed for grissly, promptly and repeatedly.

But I didn't just pray for his son's return. I prayed for his wife, his son, and for Grissly. The latter, I think, needed prayer most of all, because (from what I heard), Grissly seemed to be obsessing on himself. It was his honor, his inability to get results, that consumed him. I saw little evidence of what should have been his focus: the boy's welfare. Of course, I wasn't there for very long, so I can't be certain Grissly didn't come to realize his state of mind, and walk it back, or that there wasn't more to the story. But in case he's as stubborn as I am....

the phone rang just as i was vesting for the 10 o'clock mass. I'm not a priest, of course, just a helper, swinging incense, holding books, or toting the crucifix as needed. There's a phone in the sacristy, and I always answer it because it could be someone needing directions. Not this time.

She asked for the priest, and I said he wasn't around, but could I help? This triggered her pitiful recount of how her rent was due at noon and she was about to get kicked out onto the street and nobody could help her and she just found out her father, who's in another state, has been diagnosed with lung cancer, and then her voice dissolved into sobs.